Does robotics and artificial intelligence have a future in the healthcare space?

20 February 2018

We are in an age of rapid technological improvements. The acceleration we’re seeing is providing new capabilities, simplifying the provision of healthcare and associated services by automating processes and intervening in particular physical tasks. In some cases, sensors can provide greater safety than human hands.

Robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) are being adopted in equal measure in the healthcare space. However, the concept of a doctorless hospital is not without controversy or concern. How can we ensure that our continued adoption of technology grows sustainably and ethically?

MUST HUMAN CARE BE PERFORMED BY HUMANS?

A European Parliament Committee report on the civil law of robots[1] unequivocally states that ‘human contact is one of the fundamental aspects of human care’ and replacing humans with robots could “dehumanise caring practices”.

Similarly, it is widely accepted that people have the right to refuse to be cared for by a robot. This is particularly important for vulnerable people, such as the disabled or elderly, who may have less control over their care. However, it isn’t as simple as saying “humans are irreplaceable” in human care roles.

In many respects, robots present new opportunities for human care that humans cannot replicate. Firstly, they have physical capabilities that are useful to provide an array of physical services, such as household jobs which assist an aged person to remain independent.

Secondly, in some contexts, robots may in some respects be able to work better with people on an emotional and mental level. The Queensland University of Technology and Children’s Health Queensland are exploring the use of robots as healthy eating companions, designed to deliver non-judgemental advice.[2] It is feasible that some people may seek solace in the inability of a robot to ‘feel’, such that it reduces a person’s embarrassment or pride when seeking assistance.

THE NEED FOR A TECHNOLOGICALLY LITERATE MEDICAL PROFESSION

Technology is intervening more and more in the provision of medical services. Soon 3D printing will be commonplace in hospitals and the proliferation of medical apps is set to increase. But it is important that workforce capability and understanding grows alongside its technological counterparts. The healthcare industry must be ready to regulate and enforce the need for professionals to have specialist expertise before working with technology.

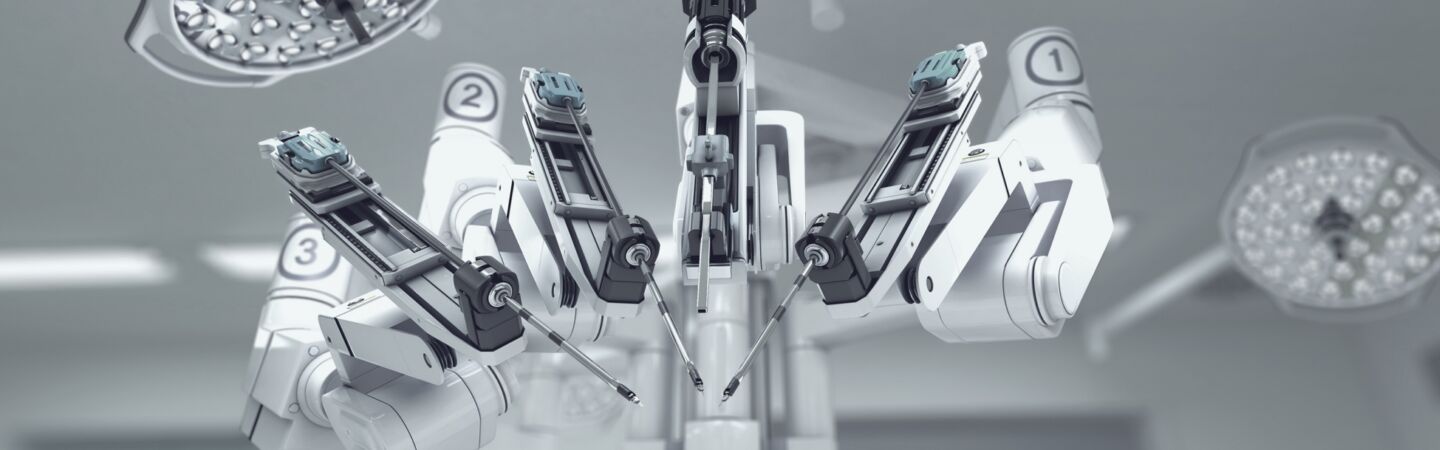

ARE WE SAFER IN THE HANDS OF ROBOTS?

There’s a widely held view that a city run on driverless cars will be safer than one with human drivers. Robots’ sensors and automation make them far less prone to error than humans. Similarly, the use of robots in the physical practice of healthcare is hailed as a step in the right direction for improved patient outcomes.

However, the use of robots is not risk-free. It simply replaces one set of risks with another. Robots, as with all technology, face cyber security risks and are prone to fault and must be maintained. Healthcare industries must consider how they can prepare for the new risk profile associated with increased use of, and reliance on, technology.

Another key issue is whether robots should be used in the practice of diagnosis. While a robot may have sophisticated sensors, allowing it to sense more than a human, robots are unlikely to develop self-learning capabilities that allow it to diagnose and treat emerging health issues.

There’s no need for aspiring health care professionals to drop out of medical school owing to the lack of future career prospects just yet. There is clearly a necessary and complementary role for humans in the practice and research in the field of healthcare.

HOW DO WE PROTECT OUR HEALTH INFORMATION?

Health information is almost universally classified as a category of sensitive information, deserving of special protection under privacy laws.[3] So how can we safeguard the collection of this information by machines which are liable to be maliciously hacked or mechanically faulty?

Investment in information protection in the healthcare sector is imperative. Strong privacy protections need to develop alongside the increased use of technology and the increased collection and sharing of health information electronically.

Another solution may lie in specifically designing technology to not collect information. While we currently live in a world where data is king, it may be worth questioning this in the healthcare space, to avoid the over-collection and exploitation of health information. We may be best served by memoryless machines.

THE SUSTAINABLE RISE OF TECHNOLOGY IN HEALTHCARE

The law is not yet ready for the widespread use of artificial intelligence in the care of humans. Crucial questions regarding how our liability and insurance laws will adapt to the use of robots are not yet answered.[4]

As such, it is imperative that the use of technology in healthcare develops incrementally, and with considerations beyond immediate benefits of cost and efficiency.

The EU Report has called for a specialist commission to answer questions in relation to robots ethics in hospitals and health care institutions. This may generate international guidance on such a complex and specialist area.

It is time for Australia to turn its mind to the same questions.

[1] European Parliament Committee report on the civil law of robots.

[2] The Queensland University of Technology and Children’s Health Queensland.

[3] By way of example, it is specifically called out in the definition of sensitive information in the data protection laws of Austria, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Denmark, Dubai, the European Union, Finland, France, Germany, India, Ireland, Luxembourg, Poland, Russia, Senegal, Serbia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

[4] See our thinking in relation to liability for/of robots.

Authors

Partner

Tags

This publication is introductory in nature. Its content is current at the date of publication. It does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should always obtain legal advice based on your specific circumstances before taking any action relating to matters covered by this publication. Some information may have been obtained from external sources, and we cannot guarantee the accuracy or currency of any such information.