Comprehensive reform package to target defective building work

24 June 2020

The NSW Parliament has passed two Acts, introduced by the NSW Government, to address concerns and issues that have arisen over a long period of time with regards to deficiencies in the quality of building and construction work across the state.

The introduction of the Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020 (DBP Act) and the Residential Apartment Buildings (Compliance and Enforcement Powers) Act 2020 (RAB Act) follows the Shergold-Weir Report into the Building and Construction industry in 2018 and the appointment of the first NSW Building Commissioner in August 2019.

Summary

The DBP Act introduces a number of additional requirements, including requirements that building practitioners:

- owe a statutory ’duty of care’ to landowners and subsequent land owners;

- are properly qualified and recognised by professional bodies, adequately insured and registered with the NSW Government; and

- issue compliance declarations that confirm their work complies with the Building Code of Australia (BCA).

These changes are designed to prevent defective building work by ensuring building practitioners have increased duties to landowners, provide the certifications required to allow principal certifiers to issue occupation certificates, and have the necessary insurance to cover their liability if they breached their duties.

The RAB Act is designed to increase the governance framework to minimise defective residential apartments and inadequate certification process in residential apartments by:

- giving the Secretary of the Department of Customer Services the power (which will be delegated to the Building Commissioner) to issue stop work orders and building work rectification orders, and prohibit the issuing of occupation certificates; and

- increasing the regulatory and enforcement powers of government to investigate and prosecute building practitioners who have engaged in defective work.

Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020

The DBP Act was first introduced as a Bill to the NSW Parliament in late 2019 and, following over 70 amendments by the Government, Opposition and crossbench, passed the Parliament on 11 June 2020. Amendments included the mandatory registration of engineers. (Access further information about the draft legislation which was released in 2019.)

Duty of care

The most significant change made by the DBP Act is the imposition of a statutory duty of care on any person who carries out construction work.

Construction work is defined to include:

- building work;

- the preparation of regulated designs and other designs for building work;

- the manufacture or supply of a building product used for building work; and

- supervising, coordinating, project managing or otherwise having substantive control over the carrying out of any of the above work.

Practitioners involved in building design, building work, the manufacturing or supply of products used for building work and supervisory roles will be required to exercise reasonable care to avoid economic loss which would be caused by defects relating to, or arising from, construction work.

If a practitioner breaches this duty of care, a property owner will be entitled to damages (regardless of whether there is a contractual arrangement to carry out that construction work).

Application

The duty of care cannot be delegated or contracted out, and it does not limit damages or other compensation that may be available where a breach of another duty occurs.

The duty of care will apply retrospectively to existing buildings and contracts, if the economic loss has become apparent within the last 10 years or after the DBP Act commenced. The duty of care also extends to subsequent owners.

Regulatory framework

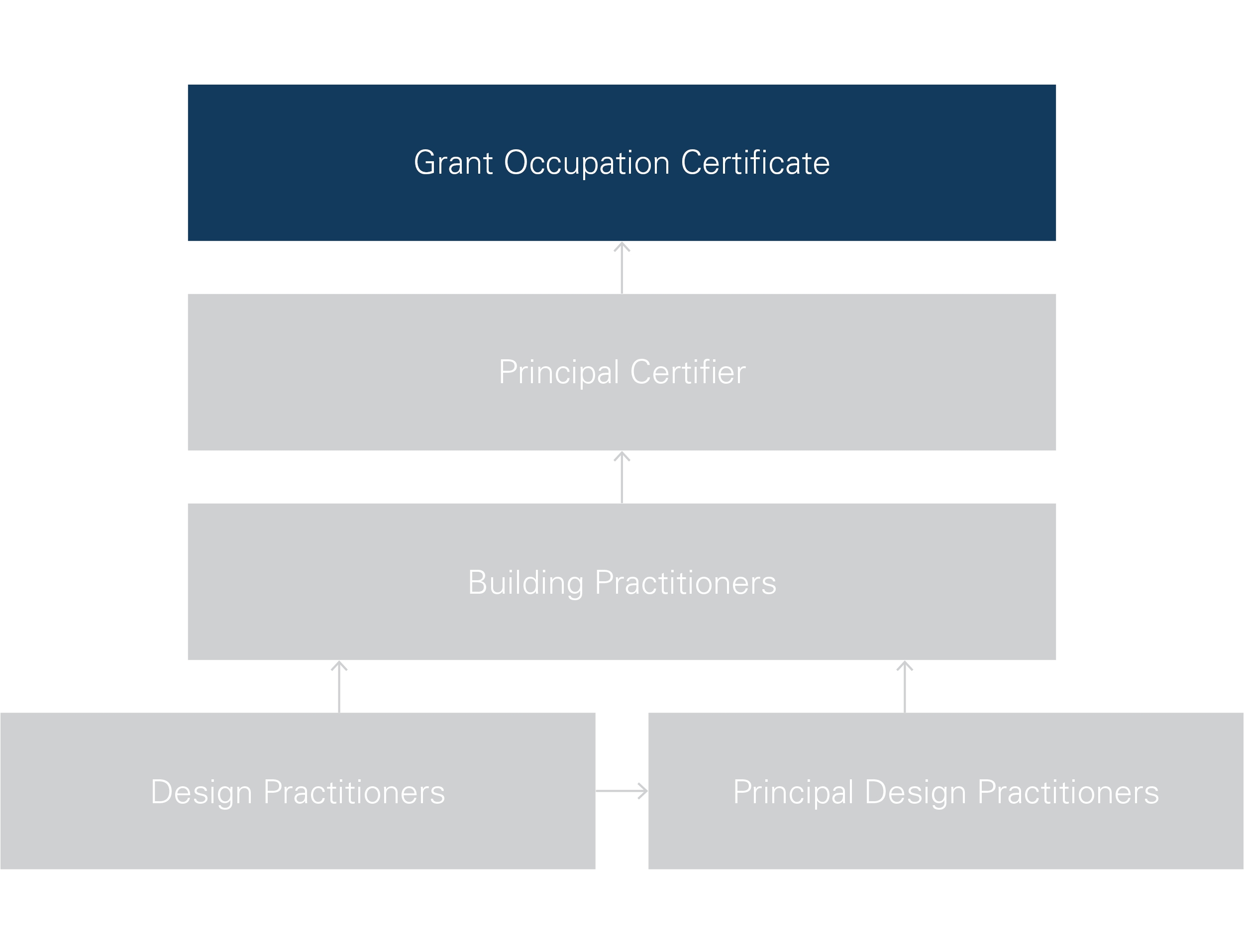

The framework means that a principal certifier can only issue an occupation certificate after it has determined and obtained all compliance declarations for the building work. The compliance declarations can be only issued by registered practitioners at various levels of the building cycle.

Registration of practitioners

The DBP Act requires the registration and regulation of design and principal design practitioners, building practitioners, professional engineers and specialist practitioners.

The DBP Act broadly defines building practitioners to include:

- anyone who is engaged, under a contract or other arrangement, to do building work, or

- if more than one person is doing the building work, the principal contractor for that work.

The broad nature of this definition means the vast majority of people engaged in building work will be required to register.

Under the registration regime, building practitioners will be required to register with the Department of Customer Service (the Department) and must be “adequately insured” before undertaking building work.

Compliance declarations

The DPB Act introduces the following concepts to implement the registration and compliance framework.

- ‘Building elements’ - which includes fire safety systems, waterproofing, load-bearing components, parts of a building enclosure, and any other mechanical, plumbing or electrical services for a building to achieve BCA compliance;

- ‘Building work’ – defined broadly, it includes the construction, alteration, repair or renovation of a building or part of a building of a class or type prescribed by the regulations; and

- ‘Regulated designs’ - which includes designs prepared for a building element for building work.

These new concepts facilitate a number of additional regulatory requirements, including requirements that:

- design and building practitioners must make ‘compliance declarations’ to the Department that building work or building elements which they have undertaken comply with the DBP Act and other required standards (including the BCA);

- any variations by a building practitioner from a regulated design for building elements or building works must be documented and new compliance declarations are sought from designers for the varied design; and

- when an application for an occupation certificate is made, notice must be given to registered building practitioners who have completed the work of the intention to apply for an occupation certificate.

Enhanced enforcement

In addition to the duty of care owed by the practitioners, the DBP Act also provides for enforcement through:

- disciplinary action against practitioners and companies involved in misconduct, including the imposition of fines between $550 and $330,0000, and imprisonment terms of up to two years for making a false compliance declaration or improper influence in relation to the issue of a compliance declaration.

- issuing of stop work orders, either unconditionally or subject to conditions.

- executive liability for contraventions of the DBP Act, if they knowingly authorised or permitted the contravention.

The DBP Act also makes numerous references to a regulatory scheme which is yet to come into effect. The proposed Regulations are anticipated to further detail:

- the insurance requirements;

- minimum qualification and continuing professional development requirements for practitioners;

- particulars required in regulated designs and compliance declarations and the form and manner in which these documents may be recorded and provided to the Department;

- additional offences as necessary to support the operation of the DBP Act; and

- the record keeping requirements for the Department and the Secretary in respect of documents collected under the Act.

Residential Apartment Buildings (Compliance and Enforcement Powers) Act 2020

The RAB Act is designed to:

- ensure developers are prevented from carrying out building work that may result in serious defects or cause significant harm or loss to the public or current or future occupiers of the building; and

- require developers to notify the Secretary of the Department of Customer Service (Secretary) 6-12 months prior to applying for an occupation certificate, to enable government to undertake quality assurance checks.

To achieve these objectives, the RAB Act enables the Secretary to:

- issue a stop work order if building work is being carried out, or likely to be carried out, in a manner that could result in a significant harm or loss to the public or current or future occupiers of the building;

- issue prohibition orders prohibiting the issuing of an occupation certificate where notification requirements have not been met, there is a serious defect or payment of a full strata bond has not been made;

- issue a building work rectification order to require developers to rectify defective building works; or

- prohibit the issuing of an occupation certificate in relation to building works in certain circumstances, including where a ‘serious defect’ exists.

Under the RAB Act, a new defect category of ‘serious defect’ has been established, which includes:

- non-compliant building elements which are attribute to a failure to comply with the BCA, relevant Australian Standard or approved plans;

- a defective building element or building product that is attributable to defective design, defective or faulty workmanship or defective materials and likely to cause an inability to inhabit or use the building, or the destruction of the building or any part of it, or a threat of collapse of the building or any part of it;

- the use of a building product which is prohibited under the Building Products (Safety) Act 2017; and

- any other defects prescribed as a serious defect under the regulations.

Application

The Act applies to ‘developers’, which is broadly defined by the Act to include:

- a person who contracted or arrange for, or facilitated or otherwise caused, the residential apartment building work to be carried out;

- if the residential building work is the construction of a building or part of a building, the owner of the land on which the work is carried out;

- the principal contractor for the work under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) (EPA Act);

- in relation to work for a strata scheme, the developer of the strata scheme under the Strata Schemes Management Act 2015; or

- any other person prescribed by the yet-to-be-released regulations.

The Act is scheduled to come into effect on 1 September 2020, and will apply to:

- ‘Class 2 buildings’ within the meaning of the BCA, which is limited to residential, multi-residential, and mixed-use buildings. Exclusions for smaller class two projects that are low risk are expected to be included in the supporting regulations; and

- all buildings either under construction or completed within the previous 10 years, ensuring protections to owners of existing defective buildings.

Regulations supporting the RAB Act are expected to be introduced later in July.

Appeals

Developers can appeal stop work orders to the Land and Environment Court. However, this appeal must be lodged within 30 days of the notice of the order being given and, unless otherwise determined by the Court, will not operate to stay the stop work order.

Increased regulatory and enforcement powers

To ensure the integrity of the residential apartment building industry, the RAB Act grants government a number of additional regulatory and enforcement powers including:

- requiring developers notify the Secretary of the Department at least six months, but not more than 12 months, before an application for an occupation certificate is intended to be made in relation to building works;

- allowing authorised officers to undertake inspections of notified building work;

- establishing penalties for the contravention of the requirements of the RAB Act, which range from infringements of $550 to $330,000;

- providing for the recovery of costs associated with compliance by a developer where there is more than 1 developer for the building work; and

- executive liability for contraventions of the RAB Act if they knowingly authorised or permitted the contravention.

It is intended that the Secretary’s powers under the RAB Act will be delegated to the Building Commissioner.

Implications

Overall, it is hoped that both the DBP and RAB Acts will have the desired effect of reinstating investor and community confidence in the construction industry, particularly Class 2 building work, without excessive time delays and cost as a consequence.

Developers and builders will need to have regard to these regulatory and governance requirements in projects going forward.

There will be challenges for the design and building practitioners in particular, including ensuring they are adequately insured in a challenging professional indemnity insurance market.

Where developers have previously enjoyed a level of flexibility in relation to materials used or final designs, the new legislation will mean more rigour in the certification process and this will need to be factored into the whole planning and delivery project timeframe.

For existing and new projects, additional modifications to development consents may be required. Developers should consider the extent to which they are giving themselves sufficient flexibility where needed in documentation that will form part of consents and which will not fundamentally affect the design outcome.

It is difficult, at this stage, to foresee all of the potential implications of the RAB Act, but it does appear that there is a risk to developers of time and cost delays if vexatious claims are made regarding defective building works. Because of this, contingencies should be factored into development program timeframes, particularly for contentious projects.

Authors

Head of Environment and Planning

Head of Gender Equality

Tags

This publication is introductory in nature. Its content is current at the date of publication. It does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should always obtain legal advice based on your specific circumstances before taking any action relating to matters covered by this publication. Some information may have been obtained from external sources, and we cannot guarantee the accuracy or currency of any such information.

Key Contact

Head of Environment and Planning